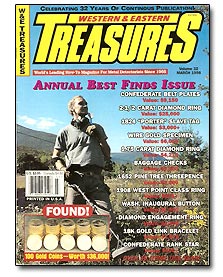

My Article on Metal Detecting Research Published in the "Western and Eastern Treasures" Magazine

Methods of Treasure Hunting Research and Exploration of White Spots on Old Maps

This article on my unusual method of researching and locating the good metal detecting sites was published in the "Western and Eastern Treasures" magazine, volume 2, page 69, in May 1998. Even though this material was published a long while ago, it still contains some useful tips on research that will never become outdated.

"Exploring 'White Spots' In Winter"

Every map, old or new, has a few areas, the "white spots", that are free of any infrastructure such as highways, houses, industrial and agricultural developments, etc. It is easy to assume that there is nothing in those uninhabited areas, especially when they appear empty on many maps. True, some "white spots" indicate impassable territories, either swamps or mountain peaks; however, most "white spots" are not only easy to walk through, but also contain webs of abandoned pathways with many productive sites situated along them. Through experience, I have realized that these empty areas often have great potential, and winter is the best time to explore them.

Since I found my first coin, a Mercury Dime, five years ago, I have become so addicted to treasure hunting that sometimes I feel guilty if I stay home on a sunny day. The excitement of my first year of metal detecting continued until heavy snowstorms came to Upstate New York, where I live. Those of you who live in the North, no doubt, understand how depressing being snowbound can be. Being impatient, I decided at least to hike the abandoned roads that I had discovered in the woods earlier that year.

During my first day's explorations, I realized that one can see much farther through the forest in winter than even in spring or fall; the worst time is in the summer, when the leaves on trees and vegetation block the view. In winter, the snowy landscape allows you to see every abnormality in the surroundings, both nearby and in the distance: depressions or mounds, remains of stone walls, perimeters of the foundations, and large lone trees standing either in the openings or in the forest.

On the same day, I spotted a barely visible road. It led to a brook, where I discovered the remains of a stone bridge. I returned to the site later, on a warmer day, and within 15 minutes after ground balancing my XLT, I unearthed four large Cents from 1830s. Later, I found two Indian Head cents, a few buttons, musket balls, and other artifacts. That was when my excitement returned, and, to my satisfaction, winter became my friend, my ally.

There is an old saying in Russia: "The wolf's life depends on its legs." In treasure hunting, one could say, "The more footwork you do, the more successful you are." As I continued doing a lot of footwork, it kept paying off very well. For example, in a five-mile region surrounding my house, I discovered four ghost towns! Two of them were established in connection with a local glass factory. This factory was operated during the early 1800s. The other two villages were developed around the blue stone quarries in mid-1800s.

In one of my favorite "white spots", I recently discovered the site of a small tavern. It was evidently in operation from the late 1700s through the mid-1800s, according to the dates on coins I have found there. Back in the summer, I had passed by the site a few times without noticing it. Now, walking there again, this time after the first snow fall, I finally saw the whole picture: a small foundation shaped as a square rock pile was situated on top of the earth mound and in the middle of a triangle formed by the two roads and the creek.

As soon as I found the first coin, a 1798 Large Cent, I knew I was at the right spot. Then out popped an 1852 3-cent piece, a 1781 Spanish Real, and six more large cents dating from 1817 to 1843. After searching the rest of the triangle, I had three more coins, Indian Head cents from the 1850s and '60s, as well as numerous buttons, buckles, musket balls, kitchen utensils, horseshoes, and pieces of clay smoking pipes.

Below are a few representatives - Large Cents, a Spanish silver Real, a 3-Cent piece, Indian Heads, of coins I found at the "virgin" site that looked like a "white spot" on the map.

Since I discovered all those sites in the "middle of nowhere", I have tried to find at least one map that would show their locations. To my surprise and excitement, after spending many hours in both local libraries and state archives, I had not found a single map revealing any traces of these "ghosts from the past." That meant only one thing to me: there were still many "ghosts" in such remote areas, and nobody would be likely to look for them (at least, not until now).

The reason for the absence of some roads and settlements on the old map might be simple: in many cases, both the local industry and its infrastructure, the dwellings for the workers and their families, and the pathways for transporting goods, would begin, flourish, decline, and be abandoned within a short period of time. Such periods of time, perhaps less than a decade, might fall into the time interval between the dates on which the lands were surveyed and the maps were drawn and published.

Some places were abandoned even before more or less accurate and detailed maps were made. For instance, the glass factory that I mentioned earlier was only in operation for just over a decade. According to the old-timers who still remembered the local historical facts, it closed down during the financial panic in 1819; thus, both the factory and the villages had been "ghosts" for 39 years when the first reliable map of the area, Beer's Map of the County, was issued for the first time in 1858. The next issue, called the Beer's Atlas, was revised and published in 1875, 17 years later. I wonder how many places, once inhabited, were left out in the "white spots" on the map when it was drawn?